Apartment investing has legs

With the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-9 not yet a distant memory, and the COVID-19 economy 2020-21 ongoing, there is little need to reiterate that returns are not guaranteed for investors, large or small.

“Cash is king” may be one retort, but in recent decades cash has also been supinely lazy, hardly working for the holder at all. In parts of Europe and Japan, depositors actually pay for the privilege of handing their money over to the bank.

The bond and stock markets also beckon, but historically feature undulating values, especially if interest rates begin to wobble higher.

Happily, for investors willing to look over the horizon for more than a few years, there is a relatively safe place to put money and get solid returns, and that is real estate, and especially apartment buildings.

Investing Through Cycles

We found that if you bought the NCREIF property portfolio in any quarter since the first quarter of 1978 and held for 10 years, you never would have lost money over the last 42 years.—The Linneman Letter, Fall, 2021

The NCREIF referenced above is the National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries, which has maintained property indices and representative portfolios for more than four decades.

Roughly the same results are obtained for investments into National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts (NAREIT) indices; that is, investors who bought and held a general NAREIT property portfolio for 10 years never lost capital, reported the Linneman Letter.

The record for three-year holding period for a general property portfolio is also very good, but not bullet proof, reported The Linneman Letter. In any year after 1978, a hypothetical investor who sold a NCREIF general property portfolio after a three-year holding period had an 11.9% chance of losing money, or a 17.0% chance of losing money on a general NAREIT portfolio.

It pays to sit and wait through the bad times.

Notably, apartment portfolios were even less risky than general property portfolios in the period following 1978.

Not only were there no money losers in that period for investors who held on to apartment portfolios for more than 10 years, only 6.9% of NCREIF apartment investors would have lost money after any three-year period, and only 8.0% of NAREIT apartment investors.

Of course, real estate investors, whether institutions or individuals, generally borrow when acquiring assets. Lenders know property is a solid-enough bet, and that allows investors to leverage. If investors can hold through the relatively rare thin times, then they can expect returns to be magnified by leverage through the good times.

Apartments

Past is sometimes prologue in investing, and in the case of apartments that seems to be true. The good performance of the apartment sector of the last 40 years is ongoing, and even accelerating. Even in the COVID-19 economy, apartment rents are rising sharply in the US, along with house prices.

As of September, national apartment rents were up about 10% from a year earlier, with little letup in sight. “On a national level, rent prices are up both short and long-term,” reported apartmentguide.com. One-bedrooms had escalated to a national average of $1,663 per month and two-bedrooms to $1,949 a month, reported the website.

The apartmentlist.com website finds even larger rent gains nationwide, and a spike in apartment lease rates starting about March.

At the root of national rising rents and house prices has been decades of suffocated supply, as local governments nationwide have generally tightened zoning restrictions and other impediments to new construction.

This de facto policy of supply suffocation is close to a national disaster for America’s renter population. Worse, the harsh reality is that fixing the supply-side will take years and even decades of building efforts and new supply—and even that, of course, is only possible if homeowners and other vested interests can be convinced to allow denser development. As it is, the new apartments that are built tend to be Class A product leasing at rents that are out of reach for the country’s working class. So-called “workforce housing” just doesn’t pencil for developers and, as such, supply of such housing is falling further and further behind demand.

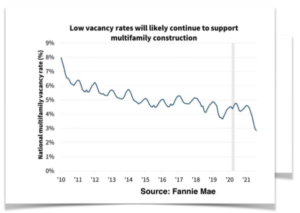

Given the choked supply, it is not surprisingly apartment vacancy rates have been declining, although there was a small blip up in empty units in September.

Moreover, the declining vacancy rates in apartment are part of a longer-term, perhaps even secular, trend:

Very likely there is no relief in sight for decreasing vacant rates and rising rents.

Housing Shortage Getting Worse, To Get Even Worse

The big fundamental in the US housing market and stock is limited new supply: “While the total stock of U.S. housing grew at an average annual rate of 1.7% from 1968 through 2000, the U.S. housing stock grew by an annual average rate of 1% in the last two decades, and only 0.7% in the last decade,” reported the Rosen Consulting Group in June, in a study prepared for the National Association of Realtors.

The Rosen Group adds, “Following decades of under-building and underinvestment, the state of America’s housing stock, which is among the most critical pieces of our national infrastructure, is dire, with a chronic shortage of affordable and available homes to house the nation’s population.”

Moreover, the outlook for a reduction in US apartment and house prices, through the normal market-corrective mechanism of greater supply, is undeniably grim, posits the Rosen Group: Given restricted supply in recent decades, the US is short about 5.5 million units. To fix the situation, US homebuilders would have to boost housing production by 60% above current levels, and keep the higher level sustained for 10 years.

Obviously, a 60% percent in production would be Herculean for any large, mature industry under the best of circumstances, but is almost certainly impossible for builders who first must gain approval from local governments to even begin construction.

The Rosen Group sensibly advocates a reduction in residential property zoning, especially the suburban standard of “R1,” also known as single-family detached housing.

“Incentivize shifts in local zoning and regulatory environments to substantially increase the quantity and density of developable residential space” advises the Rosen Group.

To be sure, much of urban America needs to be upzoned. But how many homeowners want a 10-story condo complex on their block, perhaps with ground-floor retail?

Indeed, the amount of land now occupied by single-family detached housing in major metropolitan areas is daunting. “In San Francisco, home to some of the most valuable and productive land on Earth, about 38% of residential land is R1. In Los Angeles the proportion is more than 70%. Seattle’s estimated share is more than 80%, and San Jose’s approaches 90%,” according to recent paper issued by the Department of Urban Planning at the University of California at Los Angeles Luskin School of Public Affairs.

One way to ensure that homeowners become angry voters is to suggest apartment complexes in suburban or single-family detached neighborhoods. One wag has commented, “There are no atheists in foxholes, and there are no libertarians when neighborhood property zoning is under review.”

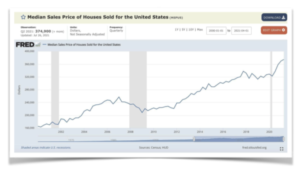

House Prices Lock Out Buyers

House prices in the US, already rising more quickly than incomes, have spiked in the COVID-19 economy, becoming ever less affordable to entire generations of Americans.

For millions of Americans who are unable to buy homes, the only real alternative is to rent. In cities such as New York, Miami and Los Angeles, more than 80% of average household income would be needed to buy an average home, according to the RealtyHop website.

Investment Outlook

Given decades of under-supply, slim prospects for new housing production, and generally expensive homes, it is likely the US apartment sector will offer steady, and perhaps even robust, returns in the coming decade.

Obviously, the US is a large nation, with many regional variations. Housing is still relatively affordable in some Midwest states, such as Kansas, Missouri, and Oklahoma, or in former industrial strongholds, such as Detroit and Cleveland.

Of course, it is nearly impossible to outthink the market, and the investment world has seen the handwriting on the wall and moved into housing and apartments.

Shrinking cap rates in residential property acquisitions show what investors are betting on.

For example, the cap rates on hotels in some US markets are running to near 10% in the first half of 2021, and on office and retail properties up towards 9% in certain softer markets, recently reported CBRE, the property-services giant.

But investors have bid logistics and multifamily housing cap rates down under 4% in some prime locations, and under 6% in most metropolitan areas.

For individuals and institutions, buying US apartment buildings is likely a safe bet through the next decade, but astute acquisitions in strong markets, deep operational experience and the ability to perform strategic property makeovers will enable investors to maximize yield and preserve capital.

The returns on apartments may take time to accumulate, but if history is a guide, the longer the hold, the higher the gain, and the smaller the risk.